I find it difficult to say when I became a Christian. Depending on how you define a Christian it could have come at different times. If a Christian is someone who attends Church, even if that is with no real desire to change in anyway, then I have been a Christian since around 2010 when I would have been fifteen years old. If a Christian is someone who attends Church with a genuine desire to know more about the faith and God, then I have been a Christian since 2011. But if we were to define a Christian as someone who has a relationship with the risen Lord Jesus then I cannot say that was true for me until late 2012, early 2013. For three years I had explored the world of the Church as I put my preconceived notions of Christianity to the test against the reality of my new found experiences. While a modern reputation of Christianity being dated and boring was sometimes validated, I was surprised to find that there was a seemingly hidden truth underneath this poor reputation. A wisdom and poignancy to the Bible that spoke into all aspects of life, whilst simultaneously opening up a whole new world.

Despite undergoing a life changing journey into the Church I was never in any doubt that Christianity in Britain was declining. This was validated when I took ‘religious studies’ at A level. One of the first things we were tasked with exploring was the current landscape of Christianity in Britain and the rise of ‘new religious movements’. It was at this time that I remember memorising some of the results from the 2001 and the 2011 census’ for my exams. The one that I have remembered to this day is the statistics for those who identify as ‘Christian’ in England and Wales. Now this is already a difficult thing to quantify. My own testimony can attest to the variety of ways one may categorise themselves as ‘Christian.’ In reality, the term could be broader still. I have a cousin who will openly tell you that he does not believe in God. He does not believe the Bible has any real authority, or that the Church is anything special. Yet he openly identifies himself as ‘Christian.’ To him, the fact that he has been baptised and brought up in (as he understands it) a Christian country, is sufficient enough reason to classify himself under such terminology. Baring in mind the potential vague interpretations for the title of ‘Christian’, 2001 saw 71.75% of England and wales identify as Christian. [1] At the time, this appeared to be a rather successful percentage to me. Certainly it was higher than I was anticipating. Yet within ten years that statistic had dropped to 59.3%. [2] Although this was far more of what I was expecting, I was shocked at the sharp decline that had taken place over such a relatively short amount of time. It also struck me that if this rate of decline were to continue, then those identifying as ‘Christian’ would have dropped to less than 50% by 2021. On the 29th November 2022 the results for the 2021 census on religion was released and confirmed my suspicions. It showed that those identifying as ‘Christian’ in England and Wales had yet again dropped to 46.2%. [3]

For nearly ten years I have wondered and theorised on why the Church was declining. I felt called to ordained ministry in the Methodist church shortly after coming to the Church and it was a source of great concern for me to think that the institution I was to devote my life to was in sharp decline. My theories have changed over the years, but the prevailing thought at the moment centres around the Churches identity in relation to society. Traditionally you will find more liberally minded Churches will seek to adapt and conform, to some degree, to the society around them. Whereas more evangelical/conservatively minded Churches will rest unapologetically on their understanding of scripture, regardless of whether that is in line with contemporary thought. Having grown up outside of the Church, I came to faith with a liberal understanding of theology and scripture. Yet routinely I found that whenever my beliefs were in contradiction to the prevailing message of the Bible, its approach was proven to be far wiser and superior than my own. This led to a key moment in my own discipleship as I prayed to God with the resolution to put as much faith in His word as I put in Him. This felt strange and wrong at the time, but caused my relationship with God to deepen in ways that I could not have predicted. I developed a more charismatic theology and and began to identify more with the title of ‘evangelical’.

The deeper I fell into this understanding of charismatic theology the more unique the Church became. It was visibly different to the world around it, and subsequently offered something that could not be found elsewhere. Yet as I entered ministerial training, I felt targeted for my charismatic evangelical theology which was viewed as the reason for the decline of the Church. I was routinely told that unless we learnt to adapt and change with the times then we would be unable to speak into the world in which we were called to serve. This was demonstrated regularly with lecturers who would seek to discredit entire books in the Bible and were uneasy using any kind of biblical vernacular feeling it was too at odds with the modern world. One lecturer took this approach so far that they no longer felt comfortable referring to Jesus as their ‘Lord and saviour.’ Another felt that the Bible was simply a flawed document that carried with it the prejudices of the time. For two years I was told that if we were to give way to this new progressive liberal understanding of scripture in a greater attempt to resemble the culture we serve, then we would experience growth. As if this was not enough, to dare to disagree was apparently cause to be targeted for what they saw as bigotry in not wanting to simply conform.

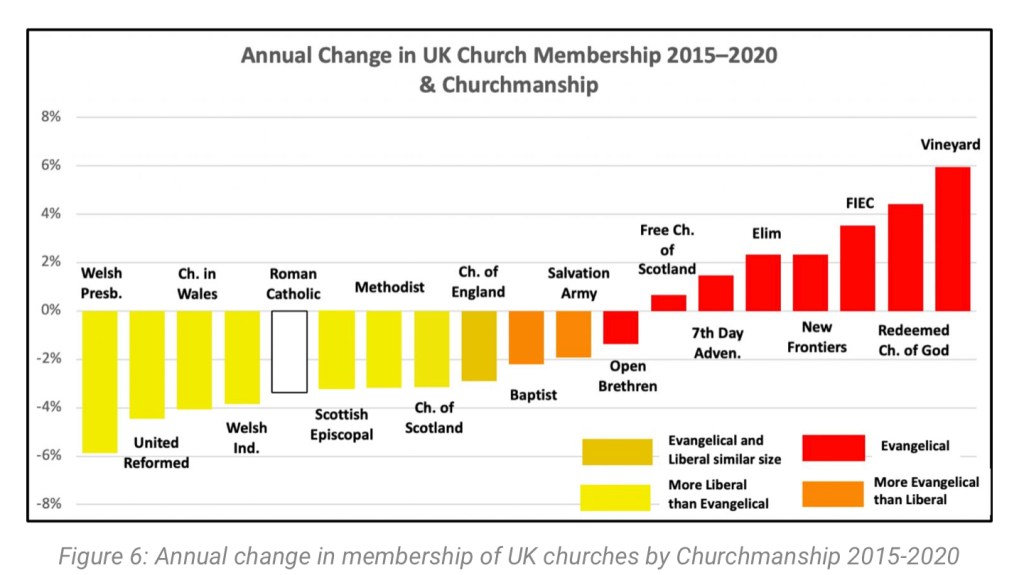

Incensed by this attitude I began exploring various Christian denominations to see which ones were experiencing growth and which ones were suffering decline. The most enlightening report came from John Hayward who had researched this very issue. In exploring the annual change in UK Church membership in various denominations from the years of 2015-2020 he compiled this graph;

In explaining his findings, John Hayward wrote that, “All the evangelical denominations are growing, except for the Brethren. By contrast, all the mixed denominations are declining, with the liberal ones declining the most.” [4] Not only does this graph show that the denominations who hold a more typically liberal and progressive theology are in sharp decline, but that those who hold to a more evangelical theology were in fact seeing growth. There is also a pattern here for older churches seeing less growth than newer ones. All the growing Churches in this graph were founded post 1900’s, aside from the Free Church of Scotland and the 7th Day Adventists. Whilst all the Churches seeing decline were founded pre 1900’s. Hayward speculates that this may be due to newer Churches still retaining some of “the fire of their founders.” [5] This suggests that there is a danger in a Church slowly turning away from the charismatic fire that once fuelled its origin, in favour of something more familiar to the time. This is arguably something that has happened to the Methodist Church. Once venerated for causing the first great rivival of this country with John Wesley (founder of Methodism) arguably being the founder of modern day Pentecostalism. Yet between the year 2000 and 2020 Methodism has declined by 50%. [6] Halfing your size within just twenty years is a very serious issue.

Now this post is not designed to be a slur against Methodism. I am a Methodist minister, I still hold much hope for its future and there are signs of growth in certain pockets of this denomination. But statistics such as these cannot be ignored, especially when a Methodist training college had so militantly defended progressive liberalism as the answer to decline. All Christian denominations need to be very careful to observe growing Churches to see what it is they are doing that is gaining favour from the Lord. 1 Corinthians 3:6-7 tells us that “neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth.”This means that any growth witnessed in the Church cannot be fully put down to the church itself, but to God who has granted them that growth. One of the fastest growing Christian churches in the UK is Elim Pentecostal church. In response to this, Elims director of Ministry, Stuart Blount said that, “at the heart of Elims mission is the message of the Gospel.” [7] This may appear to be a simple statement that could come from any church, but in reality it is a testament to the core of Elims approach. Scripture first, regardless of societies influence. Now this may make Elim appear more formidable as a church as it tends to hold stricter rules than more liberally minded churches, but perhaps this is the key to its growth. In the 1980’s a sociologist by the name of Dean Kelley suggested that strict churches were stronger than lenient ones and had a greater chance of growth. His data demonstrated that, much like here in the UK, conservative evangelical churches in USA were growing and liberal churches were declining. Partly due to the strictness of those conservative churches. [8]

Amongst all of this we must consider what message we are sending out to the wider world. If we hold to our Holy text and apply a strictness that shows we are serious about it, then we demonstrate that what we believe is worth believing. That watering it down would diminish the wonders and truth that it represents. Yet when we demonstrate that we are willing to adapt towards society to make ourselves more accessible, we suggest that what we follow isn’t all that important. We also fall into the trap of our voices aligning completely with society. When this happens the question must be asked, what is the point of the Church? If we simply say the same as the rest of the world, then why come to us? Why not just stay where you are? This was no better demonstrated to me than when my friend worked for the YMCA. He engaged regularly with drug addicts, alcoholics and the homeless and sought to do as much as he could to help them turn their lives around. The rest of his team did not share his faith, but engaged in the same meaningful work as he did. He told me one day that he was not allowed to pray with the people he talked to at the YMCA. This was a source of great frustration for him, as he believed that prayers were essential in helping many of these individuals. What frustrated him further was when he saw the church seeking to imitate what the YMCA were doing. When I asked why this would frustrate him, he told me that the YMCA were better at offering counselling to those struggling with substance abuse, but the church was better at offering spiritual help and guidance. Rather than seeking to be a less effective imitation, they should seek to support the YMCA while being the absent voice of prayer. This is a working partnership with the world around us. We support the good going on in the world, but we offer a different voice. One that upholds the scriptures as the God breathed word (2 Timothy 3:16), and one that offers prayer and spiritual guidance. In this respect we are unique, we are not an imitation, but rather an originator of something you cannot find elsewhere. We are unapologetic in what we believe and live up to a Code of conduct that accompanies those beliefs.

To tie this rant off, I am not insulting any church or denomination. I am not saying that any church is beyond renewal, or that Britain is beyond a potential revival. I am also not suggesting that any denomination is completely without merit. In fact I hope and pray for growth within all churches. So that the good they are doing may continue. So that we could reach more people and change these deeply distressing statistics that reflect such a strong decline. So that we could one day again be a majority. But in my opinion, I do not think we will see that until we return to a deeper appreciation fo the Bible and develop a more evangelical theology. This is simply my opinion.

[1] http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/shared/spl/hi/uk/03/census_2001/html/religion.stm, Accessed 29/11/2022

[2]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/articles/religioninenglandandwales2011/2012-12-11, Accessed 29/11/2022

[3]https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/religion/bulletins/religionenglandandwales/census2021, Accessed 29/11/2022

[4]https://churchmodel.org.uk/2022/05/15/growth-decline-and-extinction-of-uk-churches/, Accessed 29/11/2022

[5]https://churchmodel.org.uk/2022/05/15/growth-decline-and-extinction-of-uk-churches/, Accessed 29/11/2022

[6]https://evangelicalfocus.com/lausanne-movement/13872/christianity-in-the-uk, Accessed 29/11/2022

[7]https://www.premierchristianity.com/opinion/elim-is-one-of-the-fastest-growing-church-movements-in-the-uk-heres-why/13171.article, Accessed 29/11/2022

[8] Kelley D. (1986). Why Conservative Churches are Growing: A Study in the Sociology of Religion. Mercer University Press.

Leave a comment